1.4. First inversion#

This tutorial shows how to do the simplest inversion case, a curve fit, by setting up a custom forward operator. The function to be fitted is

with the two unknown coefficients \(A\) (a signal amplitude) and \(\tau\) (a decay time). Both \(A\) and \(\tau\) are assumed to be positive which is often the case for physical properties. The easiest way to do this is via a logarithmic transformation of the model vector (containing A and X) which is very easily done in pyGIMLi.

First we import the pygimli library under a short name pg and the numerics library numpy. Additionally, we load the plotting module of the library matplotlib. Both come along as pyGIMLi dependencies.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import pygimli as pg

We set up the modelling operator, i.e. to return \({\bf f}({\bf x})\) for

given model parameters A and X subsumed in a vector. In order to be able to

use operator in inversion, we derive from the abstract modelling base class pg.Modelling.

The latter holds the main mimic of generating Jacobian and adminstrating the

model, the regularization and so on. The only function to overwrite is

response(). If no function createJacobian is provided, the Jacobian matrix is

computed by finite differences (brute force), i.e. forward calculations with altered parameters.

class ExpModelling(pg.Modelling):

"""Exponential decay function modelling operator."""

def __init__(self, tvec, verbose=False):

"""Initialize with storing t values."""

super().__init__()

self.t = tvec

def response(self, model):

"""Model response, i.e. A*exp(-t/tau)."""

return model[0] * pg.exp(-self.t / model[1])

def createStartModel(self, dataVals):

"""Create a starting model."""

return pg.Vector([max(dataVals), max(self.t)])

The __init__ function saves the time vector and defines the parameterization, i.e.

two independent parameters (a 1D mesh with one cell and two properties).

The response function computes the function using A=model[0] and X=model[1].

The function startModel defines a meaningful starting vector that can often be

derived from the data. There are other methods to set the starting model but this

one is a default one for people who use the class and forget about a starting model.

We first create an abscissa vector using numpy and generate synthetic data with two arbitrary \(A\) and \(\tau\) values.

t = np.arange(0, 1, 1e-2)

data = 10.5 * np.exp(-t/550e-3)

We define an (absolute) error level and add Gaussian noise to the data.

error = 0.5

data += pg.randn(*data.shape) * error

Next, an instance of the forward operator is created. We could use it for

calculating the synthetic data using f.response([10.5, 0.55]) or just

f([10.5, 0.55]).

We create an inversion instance of the Marquardt type by passing the forward

operator. The scheme uses a local damping of the model update and decreases

the regularization parameter subsequently, starting with a relatively large

regularization strength to avoid overshoot.

A verbose flag can be added to provide some output the inversion.

f = ExpModelling(t)

inv = pg.frameworks.MarquardtInversion(f)

By default, model parameters are assumed positive and a logarithmic transformation is applied. Similar could be done for the data, which are by default treated linearly. We then set the absolute error level that is used for data weighting. It can be a float or a vector of data length. One can also set a relative error. Finally run yields the coefficient vector and we plot some statistics.

inv.modelTrans = "log" # already by default

inv.dataTrans = "linear" # already by default

coeff = inv.run(data, absoluteError=error, verbose=False)

print(inv.absrms(), inv.chi2())

0.42990446322168285 0.7392713899916931

We see that after 1-2 iterations the absolute rms value equals the noise level, corresponding to a chi-squared misfit of 1 as it should be the case for synthetic data. The relative rms (in %) is less relevant here, but can be for other applications. Additionally, the ranges for model and model response are given and the objective function consisting of data misfit and model roughness times lambda. Note that due to the local regularization the second term does not contribute to Phi.

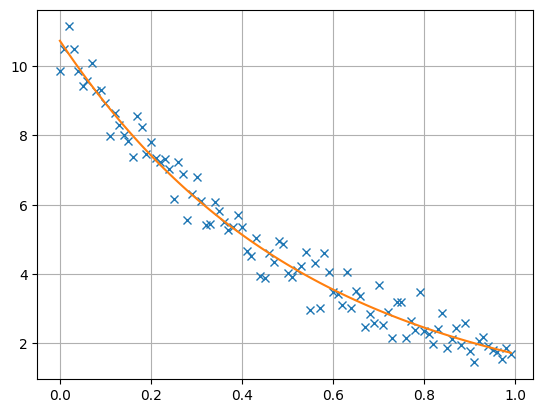

We finally create a plotting figure and plot both data and model response.

plt.figure()

plt.plot(t, data, 'x', t, inv.response, '-')

plt.grid(True)

The resulting model vector has a length of 2 and consists of the inverted A and X values that are close to the synthetic values, being equivalent within error bounds.

print(coeff)

2 [10.726088109645339, 0.543002730595385]

If you are interested which way the inversion took, you can have a look at the model history.

for i, model in enumerate(inv.modelHistory):

print(f"Iteration {i}: Model = {model}")

Iteration 0: Model = 2 [11.137945538541688, 0.99]

Iteration 1: Model = 2 [10.411964569718716, 0.5580429732451391]

Iteration 2: Model = 2 [10.725549826357849, 0.5426064638964321]

Iteration 3: Model = 2 [10.726088109645339, 0.543002730595385]